In 1989 businessman and aesthete Sergei Djavadian made a discovery: he came across a group of artists working in Yerevan in styles seldom seen anywhere in the USSR, and certainly not in Armenia. The artists were essentially collapsing the recent history of Euro-American abstraction – including Abstract Expressionism, Art Informel, Color Field painting, Minimalism, and Support-Surface, among other movements – into a bouquet of formal choices whose application signaled non-conformity and non-compliance with the regime. By this time, however, perestroika had released Soviet artists from their sequestration, allowing radical art by Russian contemporaries to come to the surface. Thus, Djavadian found his artistic soulmates, who, under his beneficence, became the painters of the Bunker Group.

The six artists Djavadian began to collect were all, in his estimation, devoting their lives to the utterances of their souls. They were not theorists but practitioners, not ideologues but individuals protective of their hard-won artistic prerogatives – non-objective styles they had been developing since the 1970s. Djavadian saw each artist as a different universe, scraping the metaphysics of human existence with his particular, even peculiar, concatenations. A jazz enthusiast, Djavadian recognized the integrity of improvised expression manifest – quite differently, but to the same intensity – in the work of each.

This “mighty Six” constituted the first generation of Bunker artists; as the collapse of the Soviet Union allowed them to travel and emigrate, they settled in Moscow, Paris, and Los Angeles, making many new associations, including with younger artists who continue the Bunker ethos.

Swimming Upstream

Sergei Djavadian’s Search For Music Of Art

SERGEI DJAVADIAN’s first discovery as a major collector of modern Armenian art was Jimi Hendrix. The young Armenian businessman growing up in USSR didn’t speak English yet but the emotions and language of American jazz went right to his head. He was looking to immerse himself in something different, against the mainstream; while most people listened to Russian socialist pop music, Sergei became “energized in an American way.”

Buying vinyl in the former Soviet Union could be an exciting if perilous adventure in those days. “To get an American LP in Russia,” Sergei explained, “was like winning the lottery.” At the beginning of the 70s, he would fly long hours to Moscow just to get LPs, and get back to work net day. In doing so, he met foreigners – “which was dangerous because American vinyl was basically forbidden by the KGB.”

As he listened to more jazz, refined his tastes, slowly built up a library of 100 LPs, and his way of thinking became more abstract, a friend suggested he would find an analogous visual experience in the underground art world. He was not worried that he would be caught. “I was used to swimming upstream, and the music inspired me to be even more strongly determined.”

Discovering art

At first Sergei had trouble understanding the music of art. “The volume of information was overwhelming.” He educated himself. He started by studying catalogs and magazines. “The truth is, I infected myself with art.”

A second turning point came in 1989 when Sergei attended the Lenz Schoenberg exhibition of postwar European art at Moscow’s Central Hall of Artists. His dream was born, to create a similar collection devoted to Armenian abstract art. More swimming upstream.

When he went to Yerevan in the fall it was to find the core of this collection. From the more than 30 outstanding artists he met he selected six who would become known as the Bunker Group: Martin Petrosian, Sev, Ashot Ashot, Armen Hadjian Rotch, Grigori Offenbach, and Kiki who served as their leader. “One of the artists, Offenbach, had a basement studio where they met to talk and be inspired by each other’s art, and one evening he said, “Let us then be the Bunker Group!”

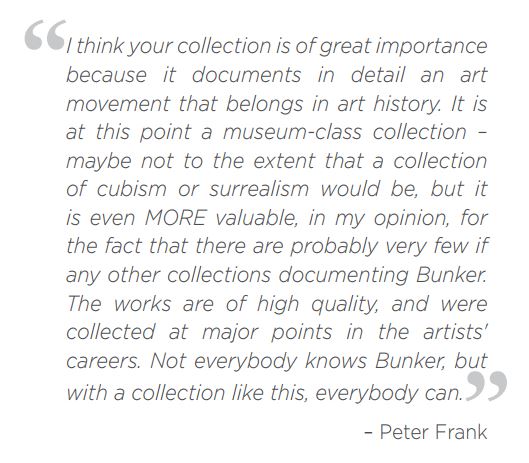

From the beginning Sergei was as impressed by the artists themselves as by their art. “I heard their souls, their conscience; I was swept away by their originality, and with no obvious influences.” These original artists/ philosophers were also the most unprotected, and Sergei wanted to provide them with an atmosphere in which they could work peacefully without commercial pressures. To do so, Sergei awarded stipends to those artists and bought some of them art studios in Yerevan. Basically he told them: Bring me in exchange as many works as you want. That’s how he created an historically valuable collection of more than 300 pieces that is split now between Yerevan and Los Angeles.

Sergei plans to let “the eagle soar,” to give maximum publicity to the artists in his collection who in his opinion are the most fundamental, expressive and honest abstract artists from their period of time in Armenia.

Artists